17 April 1990. First democratically elected parliament of Moldova starts working

17:46 | 14.04.2021 Category:

Mikhail Gorbachev, in his grand plan on the reorganization of the USSR, planned the transmission of the real power from the Communist Party to the Soviets, i.e. the bodies elected by democratic vote, beginning with the local ones and ending with the country’s leadership. Thus, in 1989, for the first time in the history of the USSR, free elections to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR took place. And in the Moldovan Soviet Socialist republic (RSSM), partially free elections were held, marked by a strong involvement of the mass media and the administration on the side of the communist candidates. Nevertheless, almost 30 per cent of the new lawmakers of the USSR were well-known people representing the national liberation movement. Among them, there were Ion Druta, Grigore Vieru, Dumitru Matcovschi, Nicolae Dabija, Veniamin Apostol, Leonida Lari and other persons involved in the processes of the society’s democratization.

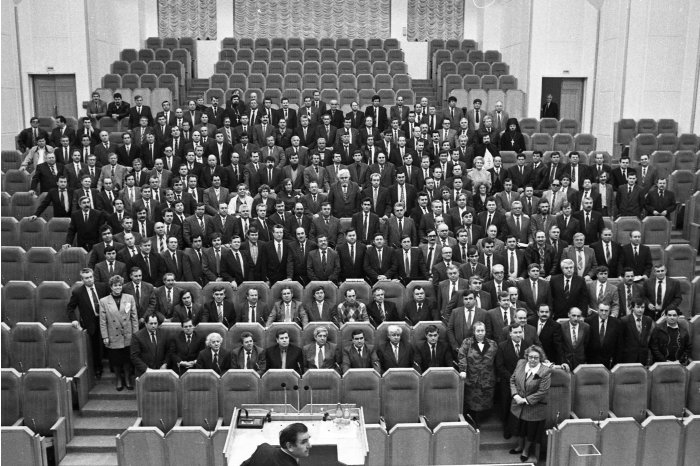

In Moldova, the free polls took place on 25 February 1990 and the repeated ones – in two weeks. The new parliament was radically different from the previous one. As many as 338 lawmakers out of those 371 ones were elected from the first time ever. A number of 358 MPs had higher education and 62 – scientific titles. A strong group of experienced jurists, representatives of the academic corps, culture people, prestigious economists came to parliament. Most of the enumerated ones were representing the Popular Font of Moldova. Another third part of the MPs were the so-called agrarians, most of them backed by the Communist Party. Another third part of the lawmakers was represented by the Unity-Edinstvo movement, which was anti-reforming and those from the eastern districts of Moldova – vehement opponents of the national revival.

The starting of the works of this parliament was a shock for the MPs with conservative opinions. The senior and moderator of the first meetings, professor Ion Borsevici introduced the term of ‘’Mister’’ in addressing and the meeting began with a blessing by father Ioan Ciuntu. Immediately, some of the radical communist lawmakers walked out of the session hall. It became clear that tough fights will be waged in this parliament.

The great victory of the team of the democrats was achieved through the finding of a consensus with the agrarians; this fact allowed, at the first phase, to carry out defining projects for Moldova’s future. Thus, the parliament’s leadership was elected, made up of Mircea Snegur, Ion Hadarca, Ion Turcanu, Dumitru Puntea. The latter was a person with deeply democratic visions and as long as he was at the head of the agrarians’ faction, it was voting reform-oriented projects.

The adoption of laws and decisions, which currently seem to be easy, came next. Yet, all these decisions were taken in the context of Moldova as part of the USSR, domination of the Communist Party in all spheres and the omnipresent control of the Soviet KGB.

One of the first decisions, which practically meant the change of the Constitution with two thirds of the votes, was the adoption of the Tricolour as state flag on 27 April. This was an unforgettable day, a holiday which comprised all settlements of Moldova, except for those checked by the separatists. The approval of a reform-oriented government, led by Mircea Druc, recognition of Lithuania’s independence, although we still were not independent, the condemnation of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact and many other courageous decisions followed.

The Declaration on Sovereignty was adopted on 23 June. This was actually a huge step towards the republic’s getting out of the USSR and subsequent proclamation of the independence. The principle of sovereignty meant that none Soviet law worked on the territory of Moldova without its ratification by the Moldovan parliament. All properties, regarded as belonging to the Soviet Union, switched to the management of Moldova. The citizenship of the Republic of Moldova was introduced.

A comprehensive process of property’s de-nationalization started on the period 1990-1991. The private property was officially recognized in the Constitution. Laws were adopted on the privatization of dwellings, small- and medium-sized enterprises, services’ infrastructure… At the same time, work was carried out to elaborate the Land Code, which was providing for the title to land.

Meanwhile, Moscova was reacting as vehemently as possible to the events in Moldova. The agrarians removed Dumitru Puntea from the leadership of their faction and set Dumitru Motpan – a conservative supporter of the preservation of the USSR. The parliament, without an efficient majority, became almost non-functional.

In August 1991, the signing of a new union treaty was scheduled in Novo-Ogaryovo – a suburb of Moscow. Moldova did not participate in the union referendum for the preservation of the USSR and implicitly, the republic gave a clear signal that it would not be part of the new union. On 19 August 1991, the chauvinistic and imperial forces made an attempt of a coup d’etat. The parliament of Moldova, as well as the one of Russia, led by Boris Yeltsin, condemned the coup d’etat just from the first day. More union republics approved the coup d’atat through their silence. In Moldova, just as in other places of the USSR, lists for the future arrests were made on those tense days. Yet, in a short period, the coup d’etat failed and political situation changed radically in the Soviet space.

In these conditions, the parliament, which condemned the coup d’etat just on the first day, ruled to hold a meeting, in order to adopt the historical Declaration of Independence. The people’s support got expression on 27 August, through the holding of a Great National Assembly, which clearly demanded the voting of the independence. In several hours, the Republic of Moldova was an independent country already and Romania recognized this fact immediately.

Next came the strengthening of the breakaway tendencies, the election of Moldova’s president by secret vote, adoption of the Land Code , which laid the foundations of a deep agrarian reform, boycotted and compromised by the agrarians, the introduction of the national currency, creation of the National Army and many other things indispensable for the good work of an independent state.

After Moldova’s self-assertion on the international stage through the recognition of the independence by almost all states of the world and the ‘’freezing’’ of the conflict in Moldova’s eastern districts, in the parliament, the demarcation line was getting between the supporters of quick reforms, which were to bring a functional market economy, and the quasi-communist agrarians and backers of the Soviet-type collective farms. The conflicts in parliament were more and more frequent and there was no longer a majority. Practically, by the autumn of 1993, the parliament became non-functional.

The Sangheli government, which represented the conservative forces, wanted snap parliamentary elections, in order to hold a comfortable majority. Only the miming of the reforms and the moving off the pro-European project of the parliament from the 1990-1992 years could easily trigger this fact. While in 1992, the U.S. Department of State called Moldova leader of the reforms in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the agrarians and their allies managed to bring a period of restoration and stagnation. There still was an issue which was to be solved at any price by the anti-reforming forces – the ratification of Moldova’s membership of the CIS, refused in the first parliament on 4 August 1993. In this way, snap parliamentary elections were announced for the spring of 1994 and the first democratically elected parliament gave up its mandate.

At present, various voices, some of whom with evil intention, the others because of lack of knowledge, criticize the first parliament with much arrogance. If one enumerates the laws and decisions adopted by this parliament, calculates their importance in the context of separation from the Soviet Empire, in the historical process of de-communization and de-Sovietization of the society, of Moldova’s self-assertion internationally, then all things adopted in the next legislative bodies are not equivalent with the value of what was produced in the 1990-1993 years.

The next parliament did not have the people with the incontestable value as the first parliament did.

The first democratically elected parliament is often called the Parliament of Independence. Yet, to the same extent, taking into account the historical importance of the process, with good reason, it can be described also as the parliament of de-communization and de-Sovietization. A good deal of the protagonists of this parliament passed away. Most of them lead a modest life, some of them are even poor and meet once per year on the Independence Day, unnoticed and ignored by the people in power. On 27 August 2021, Moldova marks the 30th anniversary of the glory moment of the generation which laid the foundations of the Republic of Moldova – adoption of the Declaration of Independence.

Chisinau, 14 April /MOLDPRES/.