August 1991: Review of a failed coup d'etat (3)

16:56 | 20.08.2021 Category:

In Chisinau, the moments of worry were replaced by an overflowing euphoric energy. First, the volunteers who guarded the state’s central institutions were assembled on the Great National Assembly Square (PMAN) and after the needed thanks on behalf of Moldova’s leadership, they left home. Just from the first day after the coup d’etat, the Presidency was competing with the Parliament in actions at the limit of lawfulness. Mircea Snegur issued a decree banning the work of party organizations at the working place. This was an almost deadly strike for the communists, as these organizations represented the basis of the party. The Presidium went further. The deputy prime minister with retrograde visions, Andrei Sangheli and the head of the Teleradio Moldova State Company, Adrian Usatii, were dismissed. The ban of the activity of the communist party in Moldova and the nationalization of its assets came next.

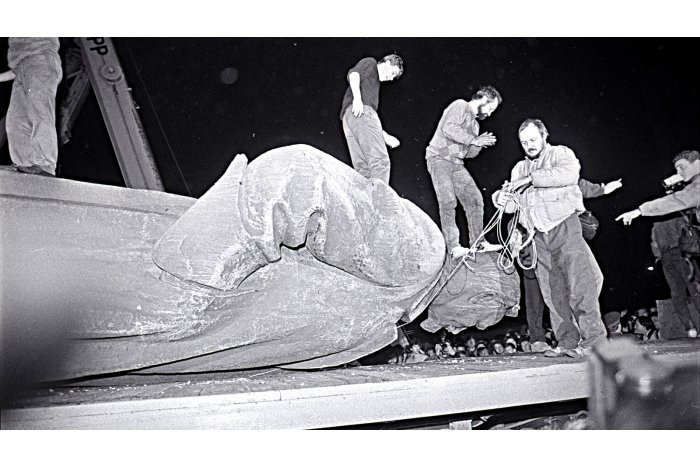

In the context, a decision was adopted banning the communist symbols and the disassembling of the communist monuments and other symbols was imposed. The names of the settlements and streets inspired from the communist ideology were to be changed. Frankly speaking, these provisions were contained in the Declaration on Sovereignty from 23 June 1990; yet, the wave of the anti-communist feelings was huge.

Also on that days, the parliament’s presidium gave instructions to the government to cease the work of the newspapers Sovetskaia Moldavia”, „Cuvântul”, „Kișiniovskie Novosti’’ and some newspapers from Moldova’s eastern districts, from Comrat and Balti, which backed the coup d’etat.

In Moldova, there was an euphoria of victory of the democracy in the USSR. The politicians were sure that the peremptory position of the republic’ s leaders would change Moscow’s attitude towards the problems faced by Moldova, especially as regards the separatism. Both Tiraspol and Comrat showed their true face during the coup d’etat. They openly backed the supporters of the coup from Moscow and Chisinau was justified to expect a support in the fight for ensuring the territorial integrity. Unfortunately, both the dying Soviet imperial centre and the democratic administration of the new Russia took over the separatist scenarios created in the KGB’s laboratories back in 1980s. This occurred also following the coup d’etat from 1993, when armed groups of Tiraspol separatists participated in the siege of Ostankino and other Russian democratic institutions. Moscow has remained a strong backer of breakaway movements from the post-Soviet area so far. Certainly, except for the ones on its territory.

The last meeting of the Congress of MPs of the USSR, held in Moscow on the next days, gave a clear-cut signal to the world: the USSR did not exist de facto. The Moldovan delegation also had a worthy behavior and informed that it would not participate in the works of this organization, as Moldova would proclaim its independence in several days.

So far, there have been more discussions about the role and importance of the coup d’etat. Was it the principal factor of the collapse of the USSR or just an accident of history? Famous analysts prefer to describe the coup d’etat as a catalyst of the process of decomposition of the Soviet empire and the death of the communism in the world.